Hypertension is one of the most important risk factors for premature morbidity and mortality in the UK. It is a major risk factor for stroke, myocardial infarction, heart failure, cognitive decline and premature death. A recent JAMA paper from 2018 labelled hypertension as “The most important risk factor for death and cardiovascular disease worldwide”.

A thorough understanding of the management of hypertension is essential for all MRCGP candidates, and it highly likely that questions will appear on this topic in the AKT and/or CSA section of the exam.

Definitions

The following definitions are commonly encountered throughout the current NICE guidelines, and it is important that MRCGP candidates are familiar with them:

| Stage of hypertension | Definition |

|---|---|

| Stage 1 hypertension | Clinic blood pressure is 140/90 mmHg or higher and subsequent ambulatory blood pressure monitoring (ABPM) daytime average or home blood pressure monitoring (HBPM) average blood pressure is 135/85 mmHg or higher. |

| Stage 2 hypertension | Clinic blood pressure is 160/100 mmHg or higher and subsequent ABPM daytime average or HBPM average blood pressure is 150/95 mmHg or higher. |

| Stage 3 hypertension | Clinic systolic blood pressure is 180 mmHg or higher or clinic diastolic blood pressure is 120 mmHg or higher. |

Malignant hypertension (also referred to as ‘accelerated hypertension’ or ‘hypertensive emergency’) is a syndrome characterised by severe a systolic BP > 180 mmHg and/or diastolic BP > 120 mmHg accompanied by end-organ damage (e.g. encephalopathy, dissection, pulmonary oedema, nephropathy, eclampsia, papilloedema and/or angiopathic haemolytic anaemia.

Risk factors for hypertension

The risk factors for hypertension can be classified into modifiable and non-modifiable groups:

| Modifiable risk factors | Non-modifiable risk factors |

|---|---|

| Obesity Excessive dietary salt intake Physical inactivity Excessive alcohol intake Stress | Older age Family history Ethnicity Gender (M>F under 56 years, F>M over 65 years) |

Diagnosing hypertension

Hypertension is usually symptomless, and effective screening is therefore very important. All adults should have their BP measured, at least once every five years up until the age of 80, and then annually over this age.

If the BP measured in clinic is 140/90 mmHg or higher, then a second measurement should be taken during the consultation. If the second measurement is substantially different from the first, then a third measurement should be taken. The lowest of the last two measurements should be recorded as the clinic blood pressure.

If the recorded clinic BP is > 140/90 mmHg, and < 180/120 mmHg, the next step in their management should be to organise ambulatory blood pressure monitoring (ABPM).

If the patient is unable to tolerate ABPM, then home blood pressure monitoring (HBPM) should be used. If HMBP is used, then patients should be appropriately educated in how to do this accurately. BP should be recorded at least twice daily, for a minimum of 4 days, and ideally for 7 days. The average value of at least 14 measurements taken during the person’s usual waking hours to confirm a diagnosis of hypertension.

Confirm the diagnosis of hypertension in people with a:

- Clinic blood pressure reading of 140/90 or higher and;

- ABPM daytime average or HBPM average of 135/85 or higher.

Assessing cardiovascular risk and end-organ damage

While awaiting confirmation of a diagnosis of hypertension, all patients should undergo a formal estimation of cardiovascular risk (QRISK2 is recommended in the current NICE guidelines, but the updated and improved QRISK3 is now available).

The NICE guidelines also recommend that these patients should be offered investigation for possible end-organ damage:

- Test for the presence of protein in the urine by sending a urine sample for estimation of the albumin:creatinine ratio and test for haematuria using a reagent strip

- Take a blood sample to measure plasma glucose, electrolytes, creatinine, estimated glomerular filtration rate, serum total cholesterol and HDL cholesterol

- Examine the fundi for the presence of hypertensive retinopathy

- Arrange for a 12-lead electrocardiograph to be performed

Lifestyle interventions

Lifestyle advice should be offered to all people with suspected or diagnosed hypertension, and it should be continued to be offered periodically. This should include advice on:

- Diet and exercise patterns

- Alcohol consumption

- Discouraging excessive coffee and caffeine consumption

- Low dietary sodium intake

- Smoking cessation

Starting antihypertensive drug treatment

Antihypertensive drug treatment should be offered to people of any age with stage 2 hypertension.

Discuss starting drug treatment in those with stage 1 hypertension and;

- Target organ damage, CVD, renal disease, diabetes, or;

- 10-year CVD risk ≥10% (and consider drug treatment in younger adults <60 years old even if CVD risk <10% as the 10-year risk may underestimate lifetime risk)

Discuss individual CVD risk and preferences for treatment, including no treatment, and explain risks and benefits before starting drug treatment.

Consider drug treatment if aged ≥ 80 years old with clinic BP ≥ 150/90

Blood pressure targets are as follows (these are based on clinic readings so add 5/5 to HBPM):

- Aged < 80 years old <140/90

- Aged ≥ 80 years old <150/90 (but use clinical judgement in those with frailty or multimorbidity)

- Use standing BP readings if postural drop ≥20 mmHg or symptoms of postural hypotension

Which antihypertensive drugs should we use?

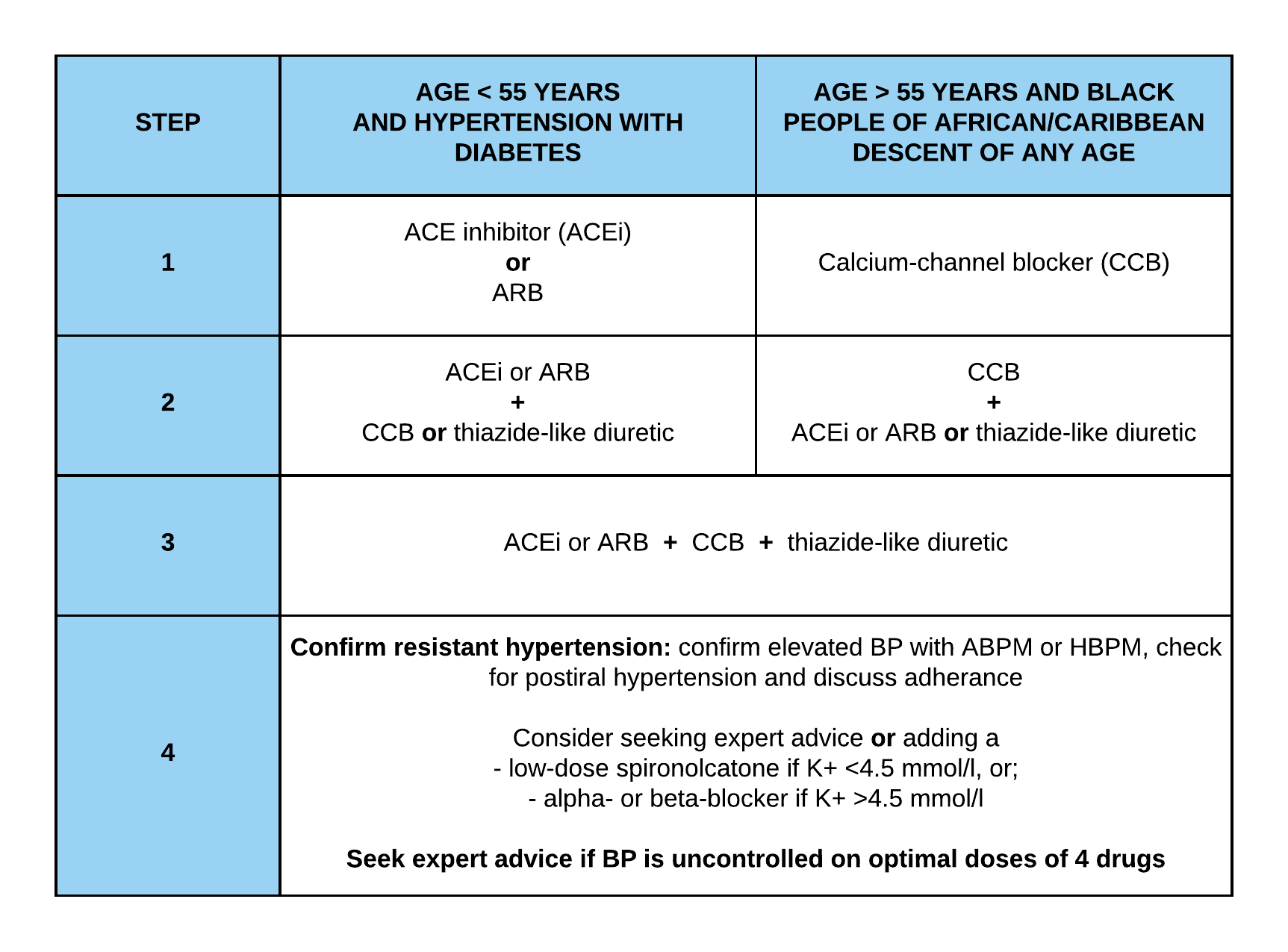

The current NICE guidelines recommend that wherever possible treatment of hypertension should be with drugs that are only taken once a day. The prescribing of non-proprietary drugs is preferable, as this will minimise costs. The choice of initial and subsequent antihypertensive drug varies depending upon the age and ethnicity of the patient, and the following algorithm is recommended:

Step 1 treatment:

Patients under the age of 55 should be offered treatment with an angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor (ACEi), such as ramipiril, or a low-cost angiotensin-II receptor blocker (ARB), such as losartan. Patients over the age of 55 and black people of African or Caribbean family origin of any age should be offered treatment with a calcium-channel blocker (CCB). ACEi and ARBS should not be used in combination to treat hypertension.

Step 2 treatment:

In step 2, if the person is taking an ACEi or ARB, then add either a CCB or a thiazide-like diuretic. If the person is taking a CCB, then add either an ACEi or ARB or a thiazide-like diuretic.

Step 3 treatment:

Before moving on to step 3 treatment, existing medication should be reviewed to ensure step 2 treatment is at optimal or best-tolerated doses and concordance reviewed. If treatment with three drugs is required, the combination of ACEi or ARB, CCB and a thiazide-like diuretic, such as chlorthalidone or indapamide, should be used. These should be used preferentially to a conventional thiazide diuretic such as bendroflumethiazide or hydrochlorothiazide.

Step 4 treatment:

Before considering further treatment confirm elevated readings with ABPM or HBPM, assess for postural hypotension and check concordance. If further treatment is required, consider further diuretic therapy with low-dose spironolactone (25 mg once daily) if the blood potassium level is 4.5 mmol/l or lower. Use particular caution in people with a reduced estimated glomerular filtration rate because they have an increased risk of hyperkalaemia. Consider higher-dose thiazide-like diuretic treatment if the blood potassium level is higher than 4.5 mmol/l. If further diuretic therapy for resistant hypertension at step 4 is not tolerated or is contraindicated or ineffective, consider using either an alpha- or beta-blocker. If blood pressure remains uncontrolled with the optimal or maximum tolerated doses of four drugs, seek expert advice if it has not yet been obtained.

Severe hypertension

Refer for a same day specialist assessment if BP ≥180/120 and;

- Signs of retinal haemorrhage/papilloedema or

- Suspected pheochromocytoma or

- Life-threatening symptoms (e.g. new-onset confusion, chest pain, heart failure or new renal failure)

If BP ≥180/120 and none of the signs above are present:

- Investigate for target organ damage ASAP

- If target organ damage present start drug treatment without waiting for ABPM/HBPM readings

- If there is no target organ damage present, repeat BP readings within 7 days

Treating hypertension in patients with medical co-morbidities

Two-thirds of all patients with a diagnosis of hypertension have a medical co-morbidity. There remains significant confusion and uncertainty on how best to manage these patients, particularly those with multiple co-morbidities.

The NICE guidelines provide advice on BP targets and preferred drug therapies in patients with hypertension and co-morbidities, such as chronic kidney disease, diabetes mellitus, atrial fibrillation. The BMJ published a very useful paper on this in 2016, and the guidance provided is summarised below:

Chronic kidney disease:

- Robust evidence exists that more intensive control of hypertension in this patient cohort reduces the risk of disease progression, particularly in those with proteinuria.

- The choice of antihypertensive drug depends upon the diabetes status and albumin:creatinine ratio (ACR).

- In patients with an ACR <30 and no history of diabetes the standard treatment algorithm above should be followed

- In patients with diabetes and/or an ACR >30 the first-line drug should be an ACEi or ARB.

Chronic heart failure:

- Patients with established heart failure should already be taking a cardio-selective beta-blocker (bisoprolol, carvedilol and nebivolol), and an ACEi or an ARB.

- If BP remains poorly controlled, a thiazide-like diuretic should be added.

- If BP control remains poor despite the addition of a thiazide-like diuretic specialist advice should be sought and the addition of spironolactone or eplerenone considered.

Atrial fibrillation:

- In patients with co-existing AF and hypertension that require rate control, consider adding either a beta-blocker (not sotalol) or a rate-limiting CCB, such as diltiazem, to any existing therapy.

- If a patient is already taking amlodipine, consider switching to a rate-controlling CCB.

The SPRINT Study and US guidelines

In 2017, the new American ACC/AHA Hypertension Guidelines were published, these redefined hypertension and hypertension treatment targets. The guidelines are heavily influenced by the Systolic Blood Pressure Intervention Trial (SPRINT) Study and may have a significant impact on future NICE guideline updates and UK clinical practice.

A short summary of the SPRINT study findings helps to explain these changes:

- SPRINT included 9,361 adults age 50 or older who had systolic pressures of 130 mm Hg or higher and at least one other cardiovascular disease risk factor.

- Approximately 28 percent of the SPRINT population was age 75 or older, and 28 percent had chronic kidney disease (CKD).

- SPRINT found that the lower target (less than 120 mm Hg) reduced cardiovascular events by 25 percent and reduced the overall risk of death by 27 percent.

- The lower systolic target (less than 120 mm Hg) also reduced cardiovascular events and saved lives in participants who had CKD.

The new US guidelines now define hypertension as follows:

- Normal: <120/80 mm Hg.

- Elevated: 120-129/<80 mm Hg.

- Stage 1: 130-139/80-89 mm Hg.

- Stage 2: >140/90 mm Hg.

This means that approximately 46% of the US population is now classified as being hypertensive.

Other major differences from the current NICE guidelines include:

- A new threshold for commencing antihypertensive medication (stage 2 hypertension, BP > 140/90 mmHg).

- HBPM instead of ABPM as the investigation of choice to confirm hypertension and for treatment titration and monitoring.

- Initiating two-drug combination therapy instead of single drug therapy if mean BP is > 150/90 mmHg.

Secondary hypertension

A secondary cause of hypertension should be considered when one or more of the following are present:

- BP remains uncontrolled with optimal or maximum tolerated doses of multiple antihypertensive drugs (e.g. at step 4 or “resistant hypertension”)

- In patients aged <40 years with evidence of target organ damage, cardiovascular disease, renal disease or diabetes mellitus

- If hypokalaemia is present

The commonest cause of secondary hypertension is renal insufficiency. Other, less common, causes include:

- Mineralocorticoid excess (e.g. primary and secondary hyperaldosteronism)

- Glucocorticoid excess (e.g. Cushing’s syndrome, corticosteroid therapy)

- Phaeochromocytoma

- Acromegaly

The clinical features of secondary causes of hypertension are summarised in the table below:

| Clinical features | Possible causes |

|---|---|

| Spontaneous or diuretic-induced hypokalaemia | Primary hyperaldosteronism (e.g. Conn’s syndrome) Secondary hyperaldosteronism (e.g. renal artery stenosis) Apparent mineralocorticoid excess (e.g. liquorice ingestion) |

| Cushingoid appearance Oligomenorrhoea Easy bruising | Cushing’s syndrome Corticosteroid therapy |

| Paroxysmal hypertension Palpitations Postural hypotension Anxiety and/or sweating Headaches | Phaeochromocytoma |

| Brow protrusion Prognathism Macroglossia Hyperpigmentation Carpal tunnel syndrome | Acromegaly |

Renal disease is the commonest cause of secondary hypertension and patients should be screened accordingly with urea and electrolytes, urine dipstick and protein/creatinine ratio. Consider referral to a renal specialist if there is evidence of CKD in patients with uncontrolled BP on four agents, or if renal artery stenosis is suspected (deteriorating renal function following initiation of an ACEi or ARB is a strong indicator of this).

If there is unexplained hypokalaemia or hypokalaemia is triggered by a low-dose of diuretic consider the possibility of hyperaldosteronism. Approximately 2-5% of patients with hypotension are thought to have a diagnosis of Conn’s syndrome. The plasma aldosterone/renin ratio (ARR) should be checked, and the patient referred to an endocrinologist if it is high. Be aware that pre-analytical variables, such as dugs, posture, and sodium intake, can affect the result, and if there is any diagnostic doubt an endocrinology referral is advisable.

Consider a referral to a cardiologist if there is a previously uninvestigated cardiac murmur present, radio-femoral delay, or marked left ventricular hypertrophy with repolarisation abnormalities on the ECG.

Further reading:

The NICE guidelines on hypertension

Treating hypertension in patients with medical co-morbidities

Systolic Blood Pressure Intervention Trial (SPRINT) Study

Many thanks to the team at www.mrcgpexamprep.co.uk for this article.

very useful

Really informative

Thanks for clear information 👍👍👍👍👍