The Royal College of General Practitioners has highlighted neonatal jaundice as a problem area for candidates in previous sittings of the MRCGP examination and it is important that candidates are familiar with the various causes, presentations and management of conditions causing jaundice in the neonatal period.

Bilirubin levels are higher in neonates than in adults because newborn babies have a higher concentration of red blood cells, which also have a shorter lifespan. It is usually a short-lived and harmless condition, but there are also some potentially serious causes that need to be assessed for.

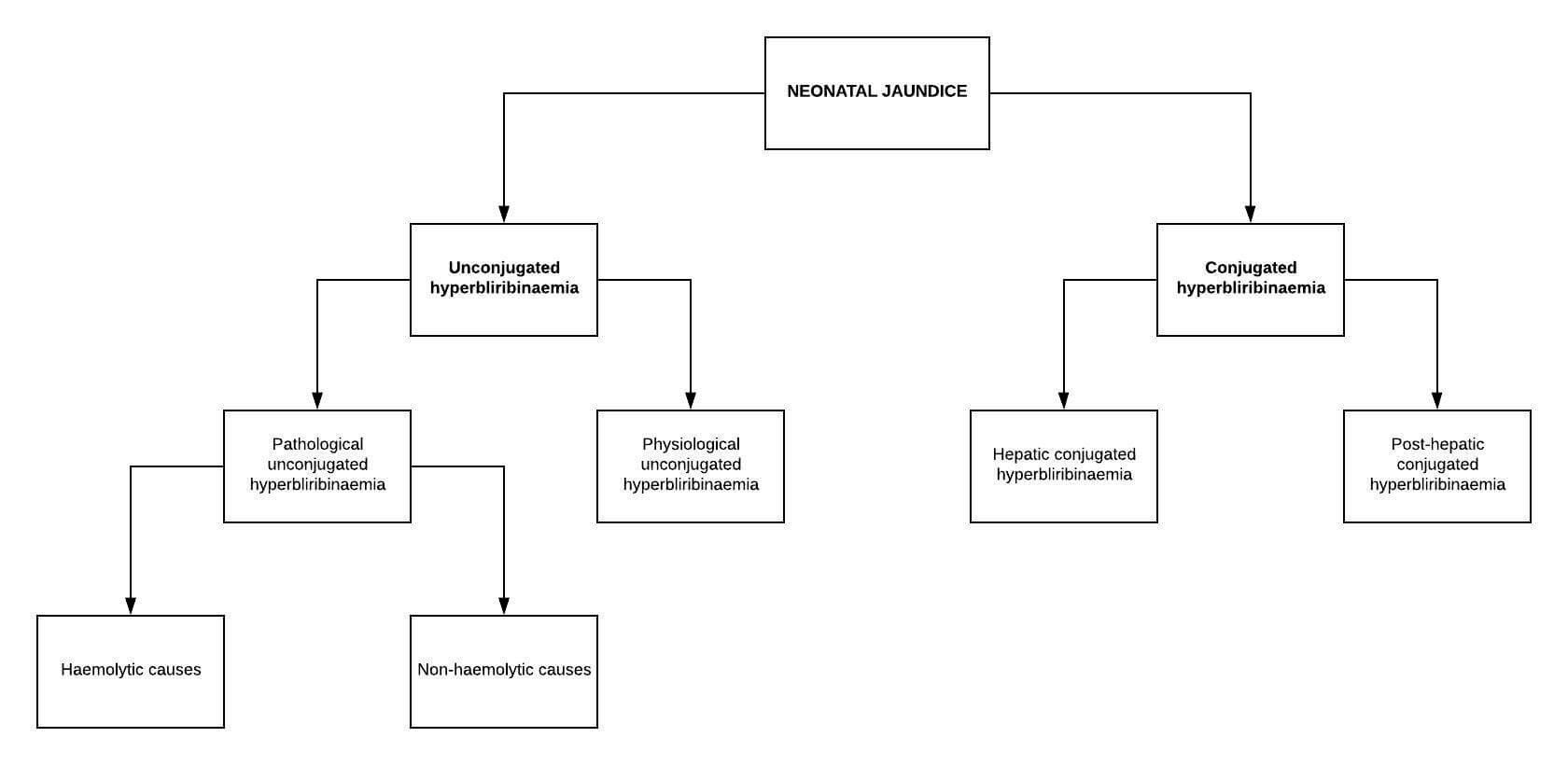

Neonatal jaundice can be subdivided into two groups:

- Unconjugated hyperbilirubinaemia (can be physiological or pathological)

- Conjugated hyperbilirubinaemia (always pathological)

Physiological jaundice

Physiological jaundice is common in neonates and is due to an elevation of unconjugated bilirubin. This results from increased red blood cell breakdown and immature liver function. It usually presents at 2 or 3 days of age, begins to disappear towards the end of the first week and has resolved by day 10. The bilirubin level does not usually rise above 200 μmol/L and the baby remains well.

Aetiology

The causes of neonatal jaundice can be subdivided according to the following categories:

| Category | Examples |

|---|---|

| Haemolytic unconjugated hyperbilirubinaemia | Intrinsic causes of haemolysis: • Hereditary spherocytosis • G6PD deficiency • Sickle-cell disease • Pyruvate kinase deficiency Extrinsic causes of haemolysis: • Haemolytic disease of the newborn • Rhesus disease |

| Non-haemolytic unconjugated hyperbilirubinaemia | Breastmilk jaundice Cephalheamatoma Polycythaemia Infection (particularly urinary tract infections) Gilbert syndrome |

| Hepatic conjugated hyperbilirubinaemia | Hepatitis A and B TORCH infections Galactosaemia Alpha 1-antitrypsin deficiency Drugs |

| Post-hepatic conjugated hyperbilirubinaemia | Biliary atresia Bile duct obstruction Choledocal cysts |

Neonatal jaundice can also be classified according to the timing with which it presents.

Early neonatal jaundice presents in the first 24 hours of life, and examples include:

- Haemolytic disease of the newborn

- Congenital infection

- Cephalhaematoma

- Gilbert syndrome

Prolonged jaundice lasts longer than 14 days in term infants and 21 days in pre-term infants, and examples include:

- Infection

- Galactosaemia

- Biliary atresia

- Bile duct obstruction

- Neonatal hepatitis

Clinical features

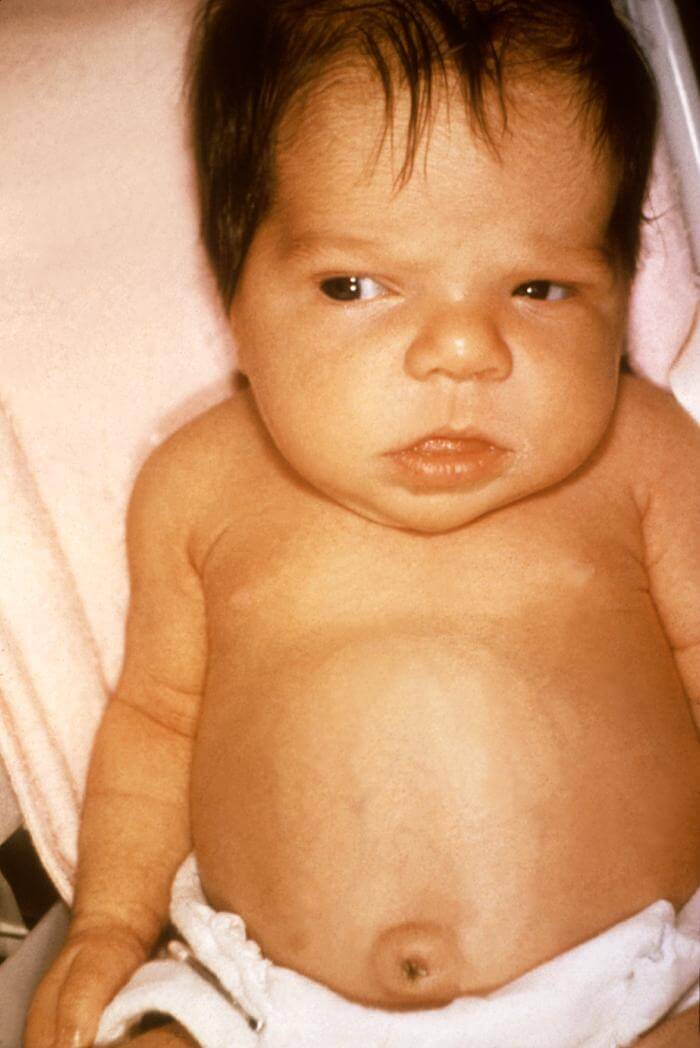

The most obvious physical sign of jaundice is a yellowish discolouration of the sclera and skin. For the eyes to be affected, the bilirubin level is usually 35μmol/L or higher, for the feet and extremities to be affected, the bilirubin is usually higher than 255 μmol/L.

Other clinical features include:

- Poor feeding

- Excessive sleepiness

- Faltering growth

- Features of the underlying cause

Visible jaundice in a neonate

Assessment of neonatal jaundice

The current NICE guidance on jaundice in the newborn provides detailed guidance on the assessment of neonatal jaundice. This is summarised below:

Review the baby’s personal child health record and hospital birth discharge documentation and talk to the parent or carer to find out about:

- Obstetric history (including the mother’s Rhesus status and blood group if known) and the baby’s gestational age at birth

- Age at onset and duration of jaundice

- Feeding history (type of feeding and whether there have been any problems with adequate intake)

- Number of wet or dirty nappies in a day (to assess the state of hydration)

- Also specifically ask about the presence of dark urine and/or pale stools

- Signs of illness (for example lethargy, fever, vomiting, significant weight loss, irritability)

- Family history of relevant conditions — for example significant haemolysis (including glucose-6-phosphate-dehydrogenase deficiency). Ask whether any siblings or close family members have required hospital treatment such as phototherapy or exchange blood transfusion for neonatal jaundice.

Examine the neonate to assess for:

- Any signs of illness, including fever

- Appropriate weight gain (compared with previous measurements if available)

- Evidence of bruising (for example cephalhaematoma following ventouse delivery)

- Evaluate the extent of jaundice

- Do not attempt to use a visual assessment of jaundice to estimate bilirubin level.

Assessing the extent of jaundice:

- Jaundice in the neonate spreads from the head downwards with increasing bilirubin levels (cephalocaudal progression). This may be because the head is better perfused than the peripheries, allowing increased bilirubin deposition.

- A visual score (Kramer’s zones) relating the extent of spread to the severity of jaundice may help in the assessment of a newborn with. However, this score cannot accurately predict the bilirubin level and has not been evaluated for community use so it should not be used alone to determine management.

Management of neonatal jaundice in primary care

The current NICE guidance on jaundice in the newborn provides detailed guidance on the management of neonatal jaundice. This is summarised below:

Arrange emergency admission (via 999 ambulance) if there is jaundice with features of bilirubin encephalopathy (for example atypical sleepiness, poor feeding, irritability).

Arrange urgent admission to a neonatal or paediatric unit (depending on local arrangements) within 2 hours if jaundice first appears at less than 24 hours of age.

Arrange urgent admission to a neonatal or paediatric unit (depending on local arrangements) as soon as possible and to be seen within 6 hours (using clinical judgement regarding more urgent referral or admission) if:

- Jaundice first appears at more than 7 days of age.

- The neonate is unwell (for example, lethargy, fever, vomiting, irritability).

- Gestational age of less than 35 weeks.

- Prolonged jaundice is suspected — that is a gestational age of less than 37 weeks with more than 21 days of jaundice; or a gestational age of 37 weeks or more with more than 14 days of jaundice.

- Poor feeding and/or concerns about weight, particularly in breastfed infants.

- Pale stools and dark urine.

For all other jaundiced neonates:

- If transcutaneous bilirubin measurements are available in primary care, record the level within 6 hours and manage according to local protocols.

- If transcutaneous bilirubin measurements are unavailable in primary care, refer to a neonatal or paediatric unit (depending on local arrangements) for measurement of a serum bilirubin level within 6 hours. Do not rely on visual assessment of jaundice to guide management.

Reassure parents and carers that:

- Neonatal jaundice is common and is usually transient and harmless.

- Breastfeeding can usually continue:

- Encourage breastfeeding mothers to breastfeed frequently (for example every 3 hours) and to wake the baby for feeds. Refer for breastfeeding support if necessary. Advise that supplementing with water or formula milk is usually not recommended.

Secondary care investigations and management

The current NICE guidance on jaundice in the newborn provides detailed guidance on the investigations and management of neonatal jaundice. This is summarised below:

In secondary care, serum bilirubin levels are usually measured in order to confirm the diagnosis and guide treatment. Neonates with significant jaundice will have investigations to determine any underlying causes, which may include:

- Full blood count and blood film – a high or low white blood cell count or thrombocytopaenia can suggest sepsis; a haematocrit of less than 45% can suggest haemolytic anaemia; an increased reticulocyte count suggests haemolysis; a peripheral blood film may show evidence of haemolysis.

- Blood group (mother and baby) – ABO incompatibility is suggested by a mother with blood group O and a baby with group A or B. Rhesus incompatibility is suggested if the mother is Rhesus negative and her baby is Rhesus positive.

- DAT (Coombs’ test) – used to diagnose ABO or Rhesus isoimmunisation.

- Liver function tests – in congenital infection, liver enzymes may be increased.

- Blood glucose-6-phosphate-dehydrogenase (G6PD) levels, taking into account ethnic origin – to check for G6PD deficiency.

- Microbiological cultures of blood, urine, and/or cerebrospinal fluid (if infection is suspected) – to look for a source of sepsis.

The choice of treatment in secondary care will depend on a number of factors, including the underlying cause of the jaundice. Options include:

- No treatment – this may be appropriate for well neonates with physiological or breastmilk jaundice and a bilirubin level below the treatment threshold.

- Treatment of any underlying illness (such as infection).

- Phototherapy – absorption of light through the skin converts unconjugated bilirubin into products that are more easily excretable in the stool and urine.

- Exchange transfusion – indicated if the baby has signs of bilirubin encephalopathy and considered if the risk of kernicterus is high or jaundice is not responding to phototherapy.

- Early surgical treatment – required for conditions such as biliary atresia.

Further reading:

NICE guidelines on Jaundice in newborn babies under 28 days

NICE Clinical Knowledge Summary on jaundice in the newborn

Header image used on licence from Shutterstock.

Thank you to the joint editorial team of www.mrcgpexamprep.co.uk for this exam tips post.

I’ve learned alot