Acyanotic congenital lesions are among the most frequently encountered cardiac abnormalities in adult imaging. Many are picked up incidentally, while others represent the long-term sequelae of childhood repairs. Sometimes, the diagnosis isn’t made until adulthood, usually because it was missed in childhood or is only now becoming clinically relevant.

Although these lesions are typically non-cyanotic, large unrepaired shunts – particularly ASDs, VSDs, and PDAs – can eventually result in pulmonary vascular disease and shunt reversal, leading to Eisenmenger physiology.

In this article, we will focus on four core lesions you are likely to encounter and should be able to recognise across modalities: atrial septal defect (ASD), ventricular septal defect (VSD), patent ductus arteriosus (PDA), and coarctation of the aorta. Each has characteristic features and practical implications, both for radiology exams and day-to-day practice.

Atrial Septal Defect (ASD)

An ASD creates a communication between the left and right atria, resulting in a left-to-right shunt. Chronic volume overload leads to enlargement of the right atrium and ventricle and, in some cases, pulmonary hypertension.

Types:

- Secundum ASD – the most common; occurs at the fossa ovalis

- Primum ASD – inferior atrial septum; associated with atrioventricular septal defects and mitral valve cleft

- Sinus venosus ASD – near the SVC or IVC; often associated with partial anomalous pulmonary venous drainage

- Coronary sinus ASD – rare; typically occurs with unroofed coronary sinus or persistent left SVC

Imaging findings:

- Chest radiograph: Enlargement of right heart chambers, prominent pulmonary arteries, and increased pulmonary vascular markings

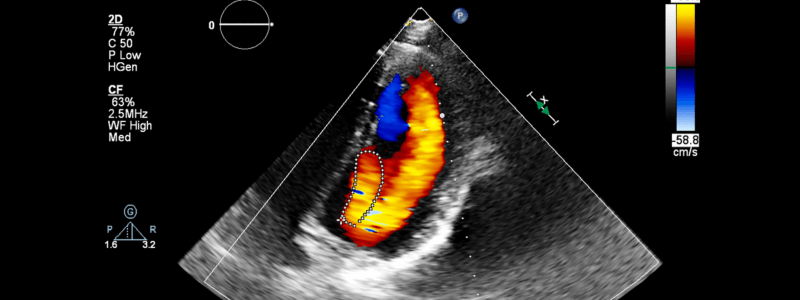

- Echocardiography: Dilated right atrium and ventricle; direct visualisation with colour Doppler; bubble contrast studies can detect small shunts

- CT/MRI: Enlargement of right-sided chambers; identification of associated anomalies; MRI can quantify shunt using Qp:Qs (a ratio >1.5 suggests haemodynamic significance)

Reporting points:

- Comment on right heart size and pulmonary vasculature

- In sinus venosus ASD, actively search for anomalous pulmonary venous return

- In primum ASD, assess the mitral valve for cleft morphology

Ventricular Septal Defect (VSD)

A VSD creates a communication between the left and right ventricles. While large VSDs are typically closed in childhood, small muscular defects may remain undetected or asymptomatic well into adulthood.

Types:

- Perimembranous: Most common; located near the aortic valve

- Muscular: Located anywhere in the septum; may be multiple

- Supracristal (outlet): Near the pulmonary valve; may cause aortic regurgitation

- Inlet: Associated with atrioventricular septal defects

Imaging findings:

- Chest radiograph: Cardiomegaly and pulmonary plethora with large defects

- Echocardiography: Left atrial and left ventricular enlargement; direct shunt visualisation on Doppler

- CT/MRI: Larger or unrepaired defects may be directly visualised; MRI can quantify shunt magnitude and assess ventricular volumes and function

Reporting points:

- Comment on chamber sizes and pulmonary findings

- Document any surgical repair or aneurysmal patch

- Distinguish high VSDs from sinus of Valsalva aneurysm or post-traumatic defects

Patent Ductus Arteriosus (PDA)

The ductus arteriosus connects the descending aorta to the pulmonary artery and normally closes shortly after birth. If the ductus remains patent, it can produce a continuous left-to-right shunt, depending on its size and the relative pressures of the aorta and pulmonary artery.

Imaging findings:

- Chest radiograph: Left atrial and left ventricular enlargement, increased pulmonary vascularity, prominent pulmonary arteries

- Echocardiography: May demonstrate continuous flow in the pulmonary artery on colour Doppler; often limited in adults

- CT angiography: Identifies a small vascular connection between the aorta and pulmonary artery

- MRI: Can assess shunt flow and Qp:Qs ratio; helpful in functional and follow-up studies – flow mapping is particularly useful when echocardiographic windows are inadequate or when other associated defects are present

Reporting points:

- State whether the PDA is isolated or associated with another congenital lesion

- Identify ductal calcification if present – this may suggest a long-standing lesion

- Assess for features of pulmonary hypertension or volume overload

Coarctation of the Aorta

Coarctation is a congenital narrowing of the aorta, typically just distal to the left subclavian artery. It may be isolated or part of a broader syndrome such as Turner syndrome or bicuspid aortic valve disease.

Imaging findings:

- Chest radiograph: Classic radiographic features include inferior rib notching from collateral vessels, the ‘figure-of-3’ sign at the site of narrowing, and left ventricular enlargement from afterload stress. These are less commonly relied upon today but still appear in exam cases.

- Echocardiography: Can estimate the pressure gradient, though transthoracic windows may be limited in adults

- CT angiography: Defines the site and severity of narrowing and maps out collaterals

- MRI: Excellent for assessing arch anatomy, flow through the stenosis, and associated aortopathy

Reporting points:

- Measure the diameter and length of the narrowing

- Describe the presence and distribution of collateral vessels

- Always document arch-sidedness and branching pattern

Eisenmenger Physiology: When Acyanotic Lesions Become Cyanotic

Some acyanotic congenital lesions, particularly large ASDs, VSDs, or PDAs, may progress to Eisenmenger syndrome if left unrepaired. Chronic left-to-right shunting leads to increased pulmonary blood flow and vascular resistance. Over time, irreversible pulmonary hypertension develops. When pulmonary pressures exceed systemic pressures, the shunt reverses (right-to-left), resulting in systemic desaturation and cyanosis.

This change marks a fundamental shift in physiology – from volume overload to pressure overload – and requires a different radiological approach.

Imaging findings may include:

- Right atrial and right ventricular enlargement

- Interventricular septal bowing towards the left ventricle

- Dilated central pulmonary arteries with peripheral pruning

- In situ pulmonary artery thrombus (especially on CT)

- Reversed or bidirectional flow through the original defect on MRI

- Qp:Qs ratio < 1 (suggestive of shunt reversal)

Eisenmenger physiology carries significant morbidity. It alters management priorities and contraindicates certain interventions, such as surgical shunt closure. Radiology reports should explicitly state when findings suggest Eisenmenger evolution and highlight any associated complications.

Summary Points

Acyanotic lesions are high-yield in both practice and the FRCR. They are often missed unless actively sought. Your role is to:

- Recognise anatomical abnormalities across modalities

- Assess their physiological impact (chamber enlargement, flow, pressure overload)

- Identify signs of previous repair

- Report in a structured, functional way

If the findings suggest a shunt, quantify it if possible. If the anatomy looks surgically altered, describe what you see and flag any signs of failure or complications.

These lesions are common for a reason: they’re clinically important, radiologically visible, and easy to miss if you’re not paying attention.

Thank you to the joint editorial team of FRCR Exam Prep for this ‘Exam Tips’ post.