Hyperthyroidism is a clinical syndrome that results from an excess of circulating thyroid hormones. It is more common in women, and the incidence increases with age. In Europe, it affects approximately 1 in 2,000 people annually.

Aetiology

Hyperthyroidism can be subclassified into:

- Primary hypothyroidism – the pathology affects the thyroid gland itself

- Secondary hypothyroidism – occurs when the thyroid gland is stimulated by excessive circulating thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH).

Graves’ disease is the most common cause of hyperthyroidism (estimates are that it causes between 50 and 80% of all cases).

Other causes of hyperthyroidism include the following:

- Toxic multinodular goitre (more common in the over 60 age group)

- Thyroiditis (e.g. De Quervain’s, silent and postpartum thyroiditis)

- TSH-secreting pituitary adenoma

- Drug-induced hyperthyroidism (e.g. levothyroxine, lithium, amiodarone

Clinical features

The symptoms and signs seen in hyperthyroidism are highly variable and can also vary according to the underlying aetiology (see below). The clinical features that can be seen in hyperthyroidism are summarised by system in the table below:

| System | Symptoms | Signs |

|---|---|---|

| General | Increased appetite Heat intolerance | Weight loss Goitre Gynaecomastia |

| Cardiovascular | Palpitations | Tachycardia Systolic hypertension Arrhythmias |

| Respiratory | Shortness of breath | Tachypnoea |

| Gastrointestinal | Abdominal pain Nausea Vomiting Diarrhoea | Abdominal tenderness |

| Neurological | Fatigue Weakness Poor concentration | Fine tremor Hyperreflexia Girdle muscle weakness |

| Ophthalmological | Diplopia Eyelid swelling Retro-orbital pain | Proptosis Lid lag Lid retraction Conjunctival injection Ophthalmoplegia |

| Dermatological | Diaphoresis Urticaria Pruritis Palmar erythema | Warm skin Hair thinning Diffuse alopecia |

| Reproductive | Loss of libido | Oligomenorrhoea Amenorrhoea |

| Psychiatric | Irritability Anxiety Psychosis |

Investigations

Hyperthyroidism is usually diagnosed based on the results of thyroid function tests.

Serum TSH the highest sensitivity and specificity for hyperthyroidism and should be the first-line investigation for the majority of patients with suspected hyperthyroidism. A normal TSH level nearly always excludes the diagnosis, but there are rare exceptions to this, for example, TSH-producing pituitary tumours and thyroid hormone resistance syndrome. If the diagnosis is strongly suspected the free T3 and T4 levels should also be requested.

Autoantibody evaluation helps to determine the underlying aetiology. Autoantibodies are most commonly seen in Graves’ disease:

- Antimicrosomal antibodies – against thyroid peroxidase (present in approximately 75% of cases of Graves’ hyperthyroidism)

- Antithyroglobulin antibodies

- TSH-receptor antibodies are commonly present in Graves’ disease, but the test is not widely available (sensitivity 98% and specificity of 99

Other useful investigations include:

- Radioactive iodine uptake scan using iodine-123 – uptake is low in thyroiditis but high in Graves’ disease and toxic multinodular goitre

- Thyroid ultrasound scan – a cost-effective and safe alternative to the radioactive iodine uptake scan

Graves’ disease

Graves’ disease is an autoimmune disease caused by the abnormal production of a TSH receptor antibody that causes the excessive production of thyroid hormones. In Graves’ disease, TSH is generally low, and levels of free T3 and T4 are markedly elevated.

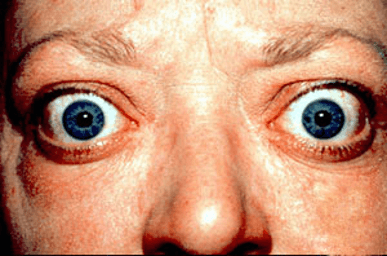

There is often a palpable goitre in Graves’ disease, and it has distinctive clinical signs that are only seen in Graves’ disease and not in other hyperthyroid conditions:

- Exophthalmos – bulging of the eye anteriorly out of the orbit

- Pre-tibial myxoedema – localised cutaneous hyaluronic acid deposits and is most commonly seen on the shins.

- Thyroid acropachy – nail clubbing and swelling of the fingers and toes.

Patient with Graves’ induced exophthalmos, image sourced from Wikipedia

Courtesy of Dr. Jonathan Trobe CC BY-SA 3.0

De Quervain’s thyroiditis

De Quervain’s thyroiditis is a self-limiting condition thought to be caused by a preceding viral illness. It is characterised by painful enlargement of the thyroid gland, fever and clinical features of hyperthyroidism. This patient has no evidence of fever, thyroid enlargement or pain, which makes this diagnosis less likely. In the hyperthyroid stage of De Quervain’s thyroiditis, TSH is generally low and free T3 and T4 are elevated.

TSH-secreting adenoma

TSH-secreting pituitary adenomas are rare tumours and account for less than 1% of all pituitary tumours. Patients often present with symptoms and signs of hyperthyroidism with a normal or high TSH and high levels of free T3 and T4. The clinical features of hyperthyroidism are sometimes milder than expected on the basis of the circulating free T3 and T4, due to the slowly progressive onset of the hyperthyroidism.

Self-administration of thyroxine

Patients self-administering thyroxine can present with symptoms and signs of hyperthyroidism and elevated free T3 and T4 levels. TSH, however, would be expected to be suppressed under these circumstances.

Management

All patients with newly diagnosed hyperthyroidism should be referred for assessment in secondary care where the underlying cause can be established, and a definitive management plan implemented.

Beta-blockers can be used in the early stages for symptom control while waiting for thyroid function to normalise. Calcium-channel blockers can be used as an alternative if patients are intolerant to beta-blockers.

There are three definitive treatment options available:

- Antithyroid drugs – carbimazole or propylthiouracil

- Radioactive iodine – given as a drink and is taken up by the thyroid gland, (recommended as the treatment of choice for Graves’ disease by NICE)

- Surgery – infrequently needed and reserved for cases not controlled by drugs and radioactive iodine.

Thyrotoxic crisis

Thyrotoxic crisis (thyroid storm) is a rare but serious and potentially life-threatening complication that develops in approximately 1-2% of patients with hyperthyroidism.

It can be caused due to a variety of factors, but potential triggers include non-compliance with thyroid medications, infection and sepsis, trauma, dehydration, myocardial ischaemia and infarction, and concurrent psychiatric illness.

The typical clinical features of thyrotoxic storm include:

- Fever

- Tachycardia (typically >140 bpm)

- Arrhythmias

- Nausea and vomiting

- Diarrhoea

- Tremor

- Abdominal pain

- Agitation and confusion

- Heart failure

- Hypotension

- Myocardial ischaemia

Investigations should be aimed at the underlying precipitant, e.g. an infection screen. Thyroid function tests should also be performed and typically show elevated T3/T4 and suppressed TSH levels. An ECG, chest X-ray, and arterial blood gas are also helpful.

Drugs used in the treatment of thyrotoxic storm include:

- Paracetamol 1 g PO/IV for pyrexia

- Benzodiazepines for sedation, e.g. diazepam 5-20 mg PO/IV

- Steroids for co-existing adrenal suppression, e.g. hydrocortisone 100 mg IV

- Antibiotics for presumed chest infection, e.g. co-amoxiclav 1.2 g IV and clarithromycin 500 mg PO/IV

- Beta-blockers, e.g. propranolol 80 mg PO

- High-dose carbimazole 45-60 mg/day PO

- Potassium iodide 200 mg IV over 1 hour (blocks release of thyroid hormones)

Other key Emergency Department management points include:

- Commence IV fluids e.g. 1-2 litres 0.9% saline

- Support and manage airway as appropriate

- Pass nasogastric tube (if the patient is vomiting)

- Referral to the on-call medical team

Header image used on licence from Shutterstock

Thank you to the joint editorial team of www.plabprep.co.uk for this article.

Thank you so much for this wonderful and timely revision resource.