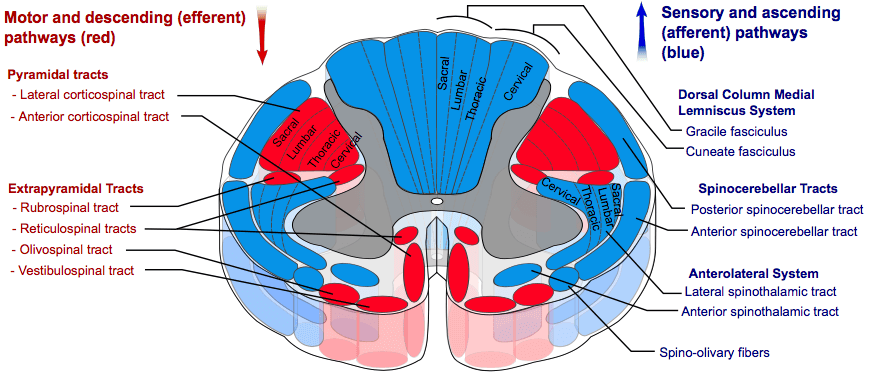

The descending tracts are pathways whereby motor signals travel from the brain to the lower motor neurons to innervate muscles and cause movement. There are no synapses in the descending pathways. All of the neurons in the descending tracts are upper motor neurons, with their cell bodies being located in the cerebral cortex or brain stem, and their axons remaining in the central nervous system.

The descending tracts can be divided into the pyramidal tracts and the extrapyramidal tracts.

Courtesy of Mikael Haggstrom CC BY-SA 3.0

The pyramidal tracts

The pyramidal tracts are efferent nerve fibres that start in cerebral cortex and carry motor fibres to the spinal cord (corticospinal tract) and brain stem (corticobulbar tract). They are involved in the voluntary control of muscles of the body and face. Both the pyramidal tracts pass through the pyramids of the medulla, hence their name.

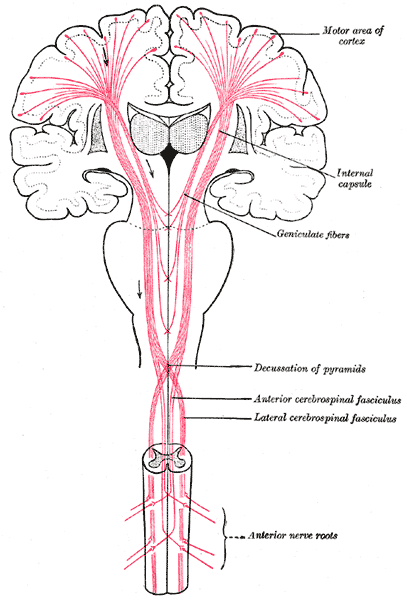

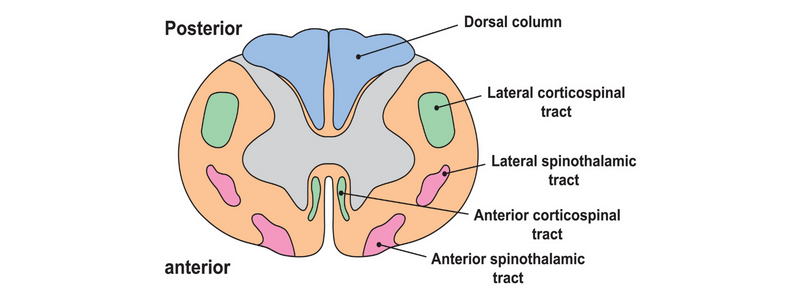

The corticospinal tract

The corticospinal tract helps to control voluntary movement. It receives inputs from the primary motor cortex (around 30%), premotor cortex and supplementary motor area (combined about 30%). It also has input from the somatosensory area, which helps to regulate the ascending tracts. It contains Betz cells, which are unique to the corticospinal tract.

The neurons then come together and pass through the posterior limb of the internal capsule. They then pass through the crus cerebri of the midbrain, the pons, and into the medulla.

In the most inferior part of the medulla, they divide into two:

- The lateral corticospinal tract – the fibres decussate and pass down the spinal cord, ending in the ventral horn at all segmental levels. From here, they supply the musculature.

- The anterior corticospinal tract – this stays ipsilateral and descends into the spinal cord. The fibres then decussate and end in the ventral horn of the cervical and upper thoracic segmental levels.

The corticobulbar tracts

The corticobulbar tracts start in the lateral part of the primary motor cortex. They also receive inputs from the primary motor cortex, premotor cortex, somatosensory area and supplementary motor area. Their path passes through the internal capsule to the brainstem.

They end on the motor nuclei of the cranial nerves, where they synapse with lower motor neurons that carry motor signals to the muscles in the face and neck. Most of the fibres of the corticobulbar tract supply the cranial nerves bilaterally. There are, however, two exceptions:

- The facial nerve – the muscles of the lower face are supplied by contralateral nerves only

- The hypoglossal nerve – only receives innervation from contralateral upper motor neurons

The extrapyramidal tracts

The extrapyramidal tracts have their origins in the brainstem and carry motor fibres to the spinal cord. They are mainly found in the reticular formation of the pons and medulla and provide control over involuntary and automatic functioning of musculature, such as muscle tone, reflexes, balance, posture and movement.

Two of the tracts do not decussate (the vestibulospinal and reticulospinal tracts), and two do decussate (the rubrospinal and tectospinal tracts).

The vestibulospinal tract

The vestibulospinal tract commences in the vestibular nuclei and then passes as two tracts (medial and lateral), remaining ipsilateral, to act on motor neurons within the spinal cord. It is part of the vestibular system and receives information from the vestibulocochlear nerve regarding head position and balance. This pathway helps to control posture, muscle tone and balance.

The reticulospinal tract

The reticulospinal tract commences in the reticular formation and then passes as two tracts (medial, arising from the pons and lateral, arising from the medulla), remaining ipsilateral, to act on motor neurons within the spinal cord. This pathway helps to control posture, muscle tone and balance in the anti-gravity muscles.

The rubrospinal tract

The rubrospinal tract commences in the red nucleus of the midbrain, decussates and descends to the spinal cord. Its actions are not clearly defined but appear to be involved primarily in the upper limb, affecting larger muscle movement as well as fine hand control.

The tectospinal tract

The tectospinal tract commences in the superior colliculus of the midbrain, where it receives afferent input from the visual nuclei. As with the rubrospinal tract, the fibres then rapidly decussate, entering the spinal cord. This tract helps to control movements of the head in response to stimuli from the optic nerve.

The corticospinal tract

The corticospinal tract helps to control voluntary movement. It receives inputs from the primary motor cortex (around 30%), premotor cortex and supplementary motor area (combined about 30%). It also has input from the somatosensory area, which helps to regulate the ascending tracts. It contains Betz cells, which are unique to the corticospinal tract.

The neurons then come together and pass through the posterior limb of the internal capsule. They then pass through the crus cerebri of the midbrain, the pons, and into the medulla.

In the most inferior part of the medulla they divide into two:

- The lateral corticospinal tract – the fibres decussate and pass down the spinal cord, ending in the ventral horn at all segmental levels. From here they supply the musculature.

- The anterior corticospinal tract – this stays ipsilateral and descends into the spinal cord. The fibres then decussate and end in the ventral horn of the cervical and upper thoracic segmental levels.

Header image used on licence from Shutterstock

For thousands of anatomy tutorials and questions visit: www.anatomyprep.co.uk

Was very useful

Best points