Urticaria is a superficial swelling of the skin (epidermis and mucous membranes) resulting in a red, raised, itchy rash that can be localised or widespread. Angio-oedema is a deeper form of urticaria that causes swelling in the dermis and submucosal or subcutaneous tissues. The name urticaria is derived from the common European stinging nettle Urtica dioica.

Urticaria is a common condition, affecting approximately 15% of people at some point during their lives. It can be acute or chronic, with the acute form being much more common. Acute urticaria is most common in children and affects women more commonly than men, particularly in the 30-60 age range. It is also more common in atopic individuals. Chronic urticaria affects between 1-2% of the population at some point during their lives, and approximately two-thirds of those affected are women. It has several genetic and autoimmune associations.

Aetiology

Acute urticaria typically occurs due to type I hypersensitivity reactions, which are allergic reactions provoked by re-exposure to a specific antigen, called the allergen. These reactions are mediated by IgE and tend to occur 15 to 30 minutes from the time of exposure to the allergen. The reaction results in the activation of mast cells in the skin resulting in the release of histamine and other mediators. These chemicals cause capillary leakage, which causes the swelling of the skin, and vasodilation causing the erythematous reaction.

An identifiable trigger is only found in around 50% of cases of acute urticaria. Common triggers include:

- Allergies, e.g. foods, bites, stings, drugs.

- Skin contact with irritants, e.g. chemicals, nettles, latex.

- Physical stimuli, e.g. firm rubbing (dermatographism), pressure, extremes of temperature.

- Viral infections.

Chronic urticaria can also occur due to type I hypersensitivity reactions, but in around 50% of affected people, type II hypersensitivity reactions are implicated. These reactions, which are sometimes referred to as cytotoxic hypersensitivity, occur when antibodies produced by the immune response, bind to antigens on the patient’s own cell surfaces.

Classification

Urticaria can be classified according to the timescale over which it occurs:

- Acute urticaria – where symptoms last less than six weeks (and usually develop and resolve very quickly, often within 48 hours).

- Chronic urticaria – where symptoms persist for six weeks or longer, on a nearly daily basis. Fewer than 5% of cases last longer than six weeks.

Chronic urticaria can be further classified as

- Chronic spontaneous urticaria – which has no identifiable external cause but may be aggravated by heat, stress, certain drugs, and infections.

- Autoimmune urticaria – which is characterised by the presence of IgG autoantibodies to the high-affinity receptor for IgE (Fc epsilon R1).

- Chronic inducible urticaria (CINDU) – which occurs in response to a physical stimulus and can be further classified according to its cause as aquagenic, cholinergic, solar, cold, heat, dermatographism, delayed pressure, vibratory, and contact urticaria.

Clinical features

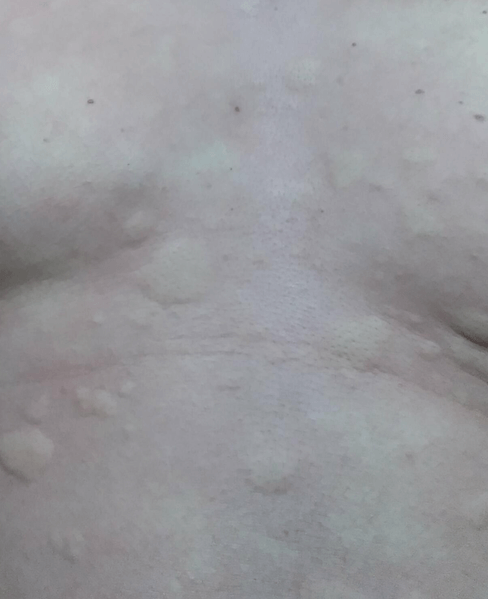

The typical skin lesion seen in urticaria is the wheal (or weal). Wheals typically consist of three features:

- A central swelling that is red or white in colour and usually surrounded by an area of redness (the flare).

- They are generally very itchy, and this is sometimes accompanied by a burning sensation.

- They are usually fleeting, with the skin returning to its normal appearance within 1–24 hours.

Wheals can vary significantly in size from just a few millimetres to lesions that can be as large as 10 cm in diameter. There may be a single lesion, or numerous lesions and lesions may coalesce to form large patches. They may also be associated with swelling of the soft tissues of the eyelids, lips and tongue (angio-oedema).

A small area comprising a number of small wheals in the region of the axilla, image sourced from Wikipedia

Courtesy of Dr. James Heilman CC BY-SA 4.0

Several large wheals on the anterior chest, image sourced from Wikipedia

Courtesy of Dr. James Heilman CC BY-SA 4.0

Numerous wheals coalescing on the forearm, image sourced from Wikipedia

Courtesy of Dr. James Heilman CC BY-SA 3.0

Investigations

The diagnosis is usually made clinically, and investigations are not usually required, particularly for acute urticaria. A detailed history should be taken to attempt to identify any possible triggers.

Chronic or recurring cases may require investigations, and these should be guided by history and presentation.

Management

For mild cases with an identifiable trigger, urticaria is often self-limiting with no treatment required. If a trigger is identified, the patient should be given clear advice on avoidance tactics.

The current NICE guidelines advise that people requiring treatment should be offered a non-sedating (second-generation) antihistamine for up to six weeks. Conventional first-generation antihistamines (e.g. promethazine and chlorpheniramine) are no longer recommended for urticaria because they are short-lasting, have sedative and anticholinergic side effects, can impair sleep, learning and performance and can interact with alcohol and other medications. Lethal overdoses with first-generation antihistamines have also been reported.

Examples of second-generation antihistamines include cetirizine, loratadine, fexofenadine, desloratadine and levocetirizine. If the standard dose (e.g. 10 mg for cetirizine) is not effective, the dose can be increased up to fourfold (e.g. 40 mg cetirizine daily). There is not thought to be any benefit from adding a second antihistamine. Terfenadine and astemizole should not be used, as they are cardiotoxic in combination with certain drugs, e.g. erythromycin and ketoconazole.

Antihistamines should be avoided where possible in pregnancy. There are no systematic studies of safety in pregnancy, and chlorphenamine is often the first choice if an antihistamine is required in this situation. Loratadine or cetirizine are preferred in breastfeeding women.

If symptoms are severe, a short course of an oral corticosteroid can be given (e.g. prednisolone 40 mg for up to seven days), in addition to the second-generation antihistamine.

Referral

The current NICE guidelines recommend referral to a dermatologist or immunologist for:

- People with urticaria that is painful and persistent (suspect vasculitic urticaria)

- People whose symptoms are not well controlled on antihistamine treatment. Secondary care treatment options include leukotriene receptor antagonists (montelukast and zafirlukast), cyclosporine, omalizumab, mycophenolate mofetil, or tacrolimus.

- People with acute severe urticaria which is thought to be due to a food or latex allergy.

- People with forms of chronic inducible urticaria that may be difficult to manage in primary care, for example, solar or cold urticaria.

The current NICE guidelines recommend referral to a clinical psychologist for people whose symptoms are adversely affecting their quality of life, for example, causing significant social or psychological problems.

Urgent hospital admission is indicated if acute urticaria rapidly develops into angio-oedema or anaphylactic shock.

Further reading:

NICE Clinical Knowledge Summary on urticaria

Header image used on licence from Shutterstock

Thank you to the joint editorial team of www.mrcgpexamprep.co.uk for this ‘Exam Tips’ post.